Inspirational People: Gary Snyder

Words and images by Luke Rees

Gary Snyder is a poet, essayist, letter writer, environmental activist and Pulitzer Prize winner.

His studies in Asian culture and languages, Zen meditation, and indigenous anthropology have inspired him to want to live a slower, sustainable life that has almost no impact on the larger ecosystem. His vision manifested itself in his home, Kitkitdizze, built in 1970 upon Snyder’s return from monastic training in Kyoto.

Kitkitdizze is a self-sufficient farmhouse-come-meditation-retreat, purposefully hidden away somewhere along the Yuba River in the California Sierras. Snyder had bought the land some years earlier, along with the poet Allen Ginsberg and a couple of other friends. Later, he bought out the other shareholders to gain sole ownership of 100 acres of untouched Sierra forest, with three-hundred-year-old stands of black oaks and ponderosa pines. Over the past fifty years, he has amassed a woodshed, a zendo, a wood-fired sauna, a small pond, a solar panel, hundreds of chickens, fruit trees, and cats. He has two sons and two step-daughters. In an interview in 1977, he told Peter Chowka that, after having finished building the house, fencing, and main water system, he and his family have a little more time to ‘sit together, dance together, and sing together.’ Snyder is now 89 and much of his vision is complete.

The word ‘Kitkitdizze’ hangs on a wooden block at the entrance to Snyder’s residence. Derived from the language of the Winton, a native American people, Kitkitdizze is a low-growing Californian aromatic shrub that can be found in the surrounding forests. Almost everything at Kitkitdizze is made from locally sourced materials. The foundation stone for the main house was sourced from the nearby Yuba River; ponderosa pines make up the main frame; and incense cedar boards up the sides. The windows were scrounged from wrecking yards, and Snyder himself laid the kitchen floor, made from local mountain-ridge sandstone. The house is one floor, low-browed, roofed with red tiles, and trimmed in an orange-red, to give the aesthetic of a Japanese farmhouse. In summer, the Sierra sunlight falls through skylights onto wooden floors and the doors are slid open to reveal Snyder’s writing table, and stacks of books. There is a small gas oven, and a wood-burning stove. In the centre of the house is a large dining table, from which squirrels take their share of fruit. At night, bats flutter in and out of the skylights.

During Kitkitdizze’s early days, water needed to be hand-pumped, and the only source of light at night was from kerosene lamps, under which Snyder wrote many poems and essays. He set up a library and would go out lecturing, using Kitkitdizze as a base camp to bring back university library books and other materials. In the 1970s, Snyder began to hold meditation sessions at the house, encouraging the growth of a new community of people committed to the land and its spiritual and ecological benefits. In his book A Place In Space, he recounts that “eventually there was a whole reinhabitory culture living this way in what we like to call Shasta Nation”.

In-between lecturing and writing, he held regular poetry readings. The famous Beat Generation poets Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg and Michael McClure visited regularly, as did his friends Kenneth Rexroth and Lew Welch, along with many other artists. His first wife, Masa Uehara said that “A natural, organic poetry salon was constantly happening in our living room […] They were in and out all the time”. Uehara did the cooking and Snyder washed the plates. Kitkitdizze’s doors were open to writers, poets, painters, spiritual seekers, and anyone with an interest in Snyder’s radical outlook.

Snyder’s vision is a protest against hundreds of years of industrial capitalism. He aims to resist the irresponsibility of mass consumerism in order to create a community of people committed to, and living with, the land. In his collection of essays, The Practice of the Wild, he draws attention to the phrase “leaving the world”, which to him means “getting away from the imperfections of human behaviour - particularly as reinforced by urban life”. But rural living is no easy ride: “Life in the wild is not just eating berries in the sunlight”.

Always pragmatic, he realised early on that he would need to work hard to realise his vision. He dismissed some traditional Zen practices, such as meditating for hours every day, because “there’s too much other work in the world to be done. Somebody’s got to grow the tomatoes”. Instead, he found religion in the land and the cultivation of it. He writes, “chisels, bent nails, wheelbarrows, and squeaky doors are all teaching the truth of the way things are”. In this way, he is a pioneer. He extended radical dialectic from social issues to animals and to plants and our interaction with the natural world. Kitkitdizze is an example of “what it would mean to live carefully and wisely, delicately in a place”.

Snyder understands that nature is so much larger than we are and that if we are to survive, we must learn to live not in nature, but alongside it. His reinhabitation of part of the Sierra forest has all been part of a long-lasting vision. He hopes that by the time of his seventh-generation grand-daughter, Kitkitdizze will still be enveloped by a fertile land, and that by that time, a whole network of bioregional homesteads and camps will have evolved.

Despite Snyder’s vast education, his erudite poetry, and his busy lifestyle, his overall message is very simple: “find your place on the planet and dig in”.

Imagery features Gary Snyder publications:

The Gary Snyder Reader: Prose, Poetry and Translations 1952-1998, Gary Snyder, Counterpoint, 2000

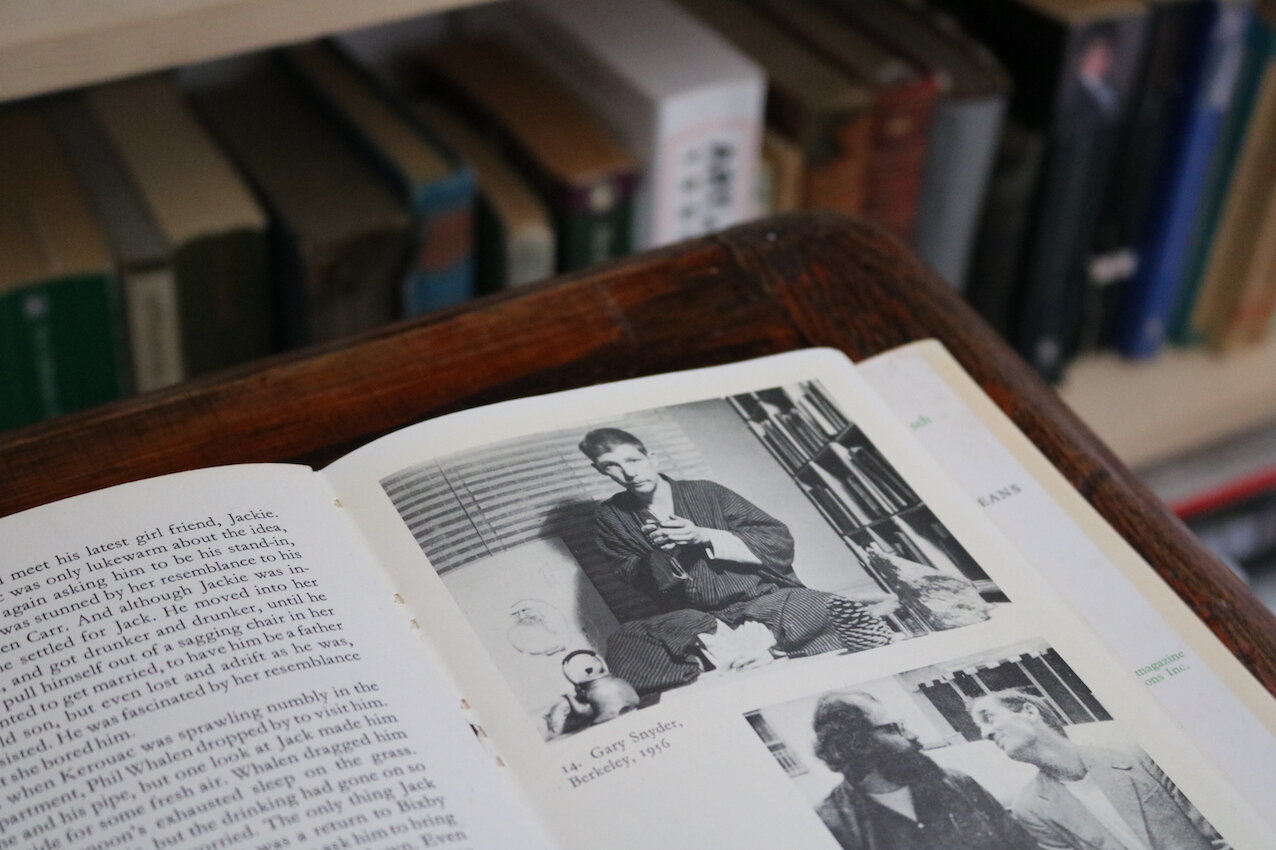

Kerouac: A Biography by Ann Charters, Andre Deutsch Limited, 1974

Earth House Hold, by Gary Snyder, New Directions Books, 1969